Consumer demand shows a need for products that have claims of “eco-friendly,” “sustainable” and “responsible”. To accommodate such demands organizations such as the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) have come up with initiatives such as the Aquaculture Dialogues and the Southern African Sustainable Seafood Initiative (SASSI).

Dialogues are standards that have been developed worldwide with farmers, retailers, NGOs, scientists and other aquaculture industry stakeholders to promote environmentally and socially responsible aquaculture. SASSI came about in November 2004, as a result of WWF South Africa’s collaboration with various networking partners across the country. SASSI’s three main objectives are: to promote voluntary compliance of the law through education and awareness, shift consumer demand away from over-exploited species to more sustainable options, and create awareness around marine conservation issues. A review was done on consumer concerns within in the aquaculture nutrition industry. An important outcome of this study was the indication that a number of interviewees were unaware of certain concerns that may have an impact on the market value of their produce of the concerns. With the WWF dialogues, the SASSI initiative and the results from the review as the driving factors, this Guide for Responsible aquafeed manufacturing and feeding (GRAF) was developed.

- Dialogues overview

- SASSI

- Fishing to Sustainable Farming

- Aquafeed Quality Challenges

- References

· the potential and detrimental environmental effect of the intrusion of fish farms into vulnerable marine and coastal areas, and

· the overall unsustainability and potential negative ecological repercussions of the dependence of wild-caught fish used as fish feed.

WWF has established best-practice methodology which are expected to be followed by industry expect the industry to follow. Among the 11 criteria there are two pertaining to nutrition, namely:

· Fish used for fish oil and fishmeal – which are often small marine pelagic species – should only come from healthy, well-managed and sustainable stocks. The industry should make every effort to find more sustainable alternatives, preferably fish offal and fish waste, plants or fish from independently certified fisheries. Fish feed companies should have traceability and sustainability policies in place to ensure the protein component is from a sustainable source.

· Genetically modified fish should not be developed for aquaculture and fish feed should be guaranteed to be free of genetically modified plants or animals.

Aquaculture has the potential to be an important source of high quality food and an economic opportunity, particularly in coastal communities and possibly in communities suffering from the deterioration of the fishing industry. WWF states that the aquaculture has the possibility of reaching sustainability, but it still has a long way to go. WWF is working with the industry to assist with moving it towards a more environmentally sustainable management that will bring more sensitive techniques, safer production and more secure long-term profit.

Dialogues OverviewIn 1994, WWF began its partnership with aquaculture by supporting a research project that compared the impact of shrimp aquaculture and shrimp trawling. Conclusion of the project resulted in the WWF identifying strategies to reduce the major impacts of shrimp aquaculture and engaging shrimp producers and government in dialogue.

Following this, WWF published a shrimp aquaculture position paper in 1997. In 1998 a sustainable shrimp aquaculture workshop was presented by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and an article was published by WWF’s Dr J Clay and Mr C Boyd in Scientific American that stressed the need for a major change in the aquaculture production system.

In 1999, in conjunction with the FAO, the World Bank and the Network of Aquaculture Centre of Asia Pacific, WWF created the Shrimp Aquaculture and the Environment Consortium (the United Nations has since joined the programme). In 2006 the consortium’s International Principles for Responsible Shrimp Aquaculture were adopted by the FAO’s Committee on Fisheries.

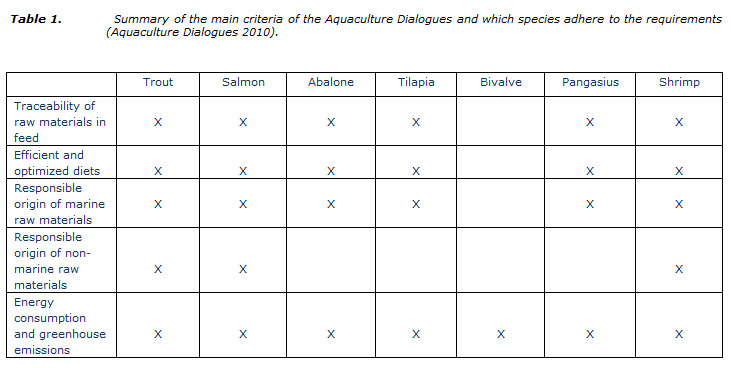

WWF then continued to engage a broad, diverse group of people in the development of standards for responsible aquaculture by starting eight roundtables referred to as the Aquaculture Dialogues. Since 2004, more than 2000 people including academics, conservationists, farmers, government officials and others continue to participate in the dialogues. The standards that have been created focus on minimizing the main negative environmental and social impacts of abalone, clams, tilapia, mussels, scallops, oysters, Pangasius, freshwater trout, salmon, shrimp, Seriola and cobia. When finalized, these standards will be handed to the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), which will be responsible for working with independent, third parties to certify farms that meet the requirements of the standards. Below is a representation of the main criteria for the feed related principles (Table 1). Each species has a set of unique standards that have been created in collaboration with farmers and other stakeholders in the industry.

Many of the world’s major fishing stocks have been depleted and in some cases have collapsed due to unsustainable fishing. Even though the future for some of the threatened marine ecosystems remains uncertain, the seafood industry has realised that change is needed in its practices to ensure long-term survival of the industry.

SASSI was initiated by WWF South Africa in association with other networking partners in November 2004. It was created to educate participants in the seafood trade – from wholesalers to restaurants, to all consumers – about the challenges facing our marine resources in terms of sustainability. The initiative builds on an earlier project that sought to educate restaurant dealers on the Marine Living Resources Act and other marine conservation issues in KwaZulu-Natal.

WWF’s Sustainable Fisheries Programme was established in 2007. The programme recognises that developing a sustainable seafood industry requires a holistic approach. It was done by addressing all aspects of the supply chain – from the fisherman’s hook to the final product that consumers buy at the fish shop or restaurant. This new programme closed the loop from boat to plate by combining the SASSI and the Responsible Fisheries Programme (RFP).

SASSI has three primary objectives:

· Promote voluntary compliance of the law through education and awareness

· Shift consumer demand away from over-exploited species to more sustainable options

· Create awareness around marine conservation issues

The SASSI consumer guide consists of three sections i.e. Green, Orange and Red listed species. Each section has a different meaning. The Green Listed species are considered to be sourced from a relatively healthy and well-managed population that can sustain the current fishing pressure. Some green species are not targeted by any particular fishery, but are managed as a sustainable by-catch. The green list species are those that consumers are encouraged to buy due to the fact that they are considered to be best managed and the most sustainable choice available to the consumer.

The Orange Listed species are those that have concerns associated with them, either due to poor stocking status, distressing population trends or as a result of other negative environmental related issues related to the fishery that the species are caught in. It is legal for registered commercial fisheries and retailers to sell these orange-listed species, although an increase in demand in these species can compromise the sustainability of the supply due to one or more of the following reasons:

· The species may currently be rare due to overfishing

.· The fishery that catches them may damage the environment through the method used and/or high bycatch.

· The biology of the species makes it vulnerable to overfishing, or it may not have been adequately studied, but it is likely that this species will be unable to sustain heavy fishing pressure based on information for related species

.Due to these reasons consumers are encouraged to consider the implications of choosing a fish from the orange list, and to rather choose an alternative from the green list.

The Red Listed species are those species that are either considered to be unsustainable or illegal to sell or buy in South Africa, according to the Marine Living Resources Act. Some of these “no-sale” species included on the Red List are important recreational species that would not be able to handle the pressure of commercial fishing, and may therefore only be caught for one’s own enjoyment and use, subject to the possession of a valid recreational fishing permit and other restrictions that may apply (such as daily bag limits, closed seasons and minimum sizes). Consumers should thus never buy these species.

Recently, aquaculture species have been added to the SASSI list. Most of the species were placed on the orange list because of a number of reasons. Each species is scored according to an internationally-accepted standard which determines on which list it is placed.

*Farm species on the Green list:

· Kob, Dusky (Argyrosomus japonicas) (farmed on land only)

· Mussels, Blue (Mytilus galloprovincialis)

· Mussels, Green Lipped (Perna canaliculus)

· Oysters, Pacific (Crassostrea gigas)

* Farm species on the Orange list::

· Abalone (Haliotis midae)

· Catfish, African Sharptooth (Clarias gariepinus)

· Kob, Dusky (Argyrosomus japonicas) (farmed in ’at sea’ cages)

· Pangasius (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus)

· Salmon, Atlantic (Salmo salar)

· Yellowtail (Seriola lalandi) (farmed in ’at sea’ cages)

*For the most current listing refer to www.wwf.org.za/sassi

Fishing to Sustainable Farming

The South African aquafeed industry contributes to less than 0.05% of the South African animal feed industry. Although there is good access to quality bulk feed ingredients, access to specialised ingredients and specialised feed manufacturing may be limiting factors, especially for juveniles and carnivores. Despite of low demand the local aquafeed industry’s for fish meal and fish oil, dependence thereupon remains a global challenge that are receiving priority attention on research, regulatory and commercial levels. In 2006 nearly half of the world’s total supply of aquatic organisms – 51.7 million metric tons – was produced by farmers for human consumption (FAO, 2009). In 2002 (FAO, 2002) it was predicted that at the current rate of production, nearly 65% of the world’s aquatic organisms will be produced on fish farms. Approximately one-third of the organisms produced rely on the inclusion of fishmeal (FM) and fish oil (FO) in their diet (Tacon & Metian, 2009).

The main criticism levelled at aquaculture is that several units of wild fish biomass are required to produce one unit of farm fish making it unsustainable, given the forecasted expansion of the industry (Pauly et al. 2003; Volpe, 2005; Clover, 2006; Stier, 2007; Allsopp et al,. 2008; Pauly, 2009). The counter argument is that levels of FM and FO in aquafeed have dropped significantly over the past decade and that the general global consumption of FM and FO by aquaculture has levelled off (Jackson, 2010). Both arguments are essentially correct (Welch et al., 2010). Currently more complex techniques are being developed for assessing the environmental impacts of food production in a more sophisticated way, namely: Life Cycle Analysis, Ecological Foot printing, Energy Flow Analysis, Primary Productivity Required and Virtual Water Flow Analysis.

In an article written by Welch et al (2010), To move beyond the FIFO debate, less often considered perspectives are examined:

· the necessity of aquaculture;· the environmental merits of aquaculture

· the prospects for sustainable aquaculture.

The industry has recognized for a number of years ago that much needs to be done to ensure a more sustainable future for aquaculture (Hardy, 1999): research needs to continue in alternative feed ingredients (Naylor et al., 2009), on-farm husbandry practices need to improve and develop (Tacon et al., 2010) and better small pelagic fisheries management (Alder et al., 2008).. Additionally, there is a need to improve the process of feed manufacturing. Currently the technology that is used consumes large amounts of energy and produces significant amounts of pollution (Tydemers et al., 2007). There are still concerns about the increasing use of low value “trash” fish as direct feed in the Asia-Pacific region (Tacon & Metian, 2009) along with the change of fish suitable for human consumption to non-food uses (Tacon et al., 2010).

However, aquaculture does have a benefit that justifies the use of small pelagic fish – by providing a high quality source of animal protein it generates significant employment and economic activity in rural coastal areas (Tacon et al., 2010). Aquaculture is also less demanding on natural resources than commercial fisheries and terrestrial animal farming (Welch et al., 2010). Finally, as demonstrated by the falling FIFO ratios and increasing production, the aquaculture industry is moving away from its dependence on FM and FO.

Aquaculture is progressing towards an increased sustainability. The industry is still too dependent on marine sources of protein; however, it has efficiency advantages that balance out this dependence relative to other forms of animal production. The research into alternatives for FM and FO has shown signs of success, proving that improvement in environmental performance will continue as the industry grows (Welch et al., 2010).

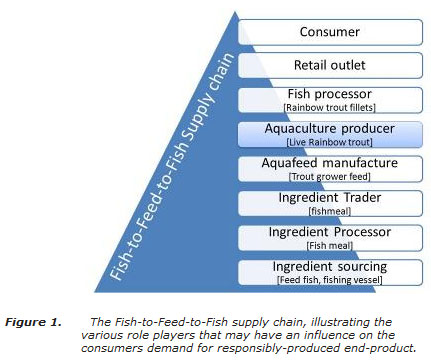

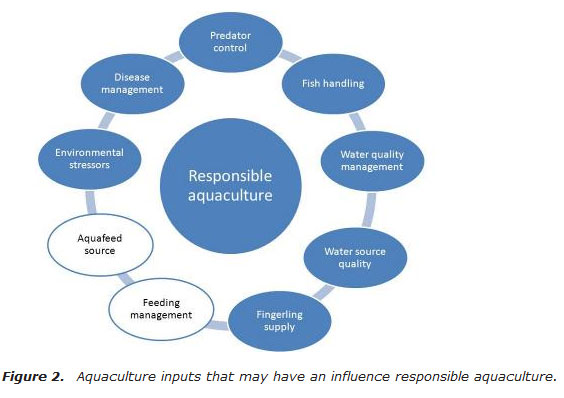

From these, aquafeed sourcing and feeding management may have a major influence in the realization of responsible aquaculture. It is further complicated by large differences in ingredient sourcing, formulation and manufacturing capacity between various commercial aquafeed manufacturers, and on-farm feed processors or “home-mixers”. In addition, specific aquaculture sectors may ultimately be compromised by regulatory loopholes.

The same applies for aquaculture producers with inevitable differences in farm set-ups, farm workers expertise, dedication and practical management style, to that lacks formal auditable management systems for sourcing aquafeed and selecting an appropriate feeding strategy for on-farm application.

For responsible end-product realisation, formal systems and practises ideally need to be put in place and externally audited on a regular basis (logistics of establishing and maintaining such systems should however not complicate farm management, but should aim to identify ways of improvement.

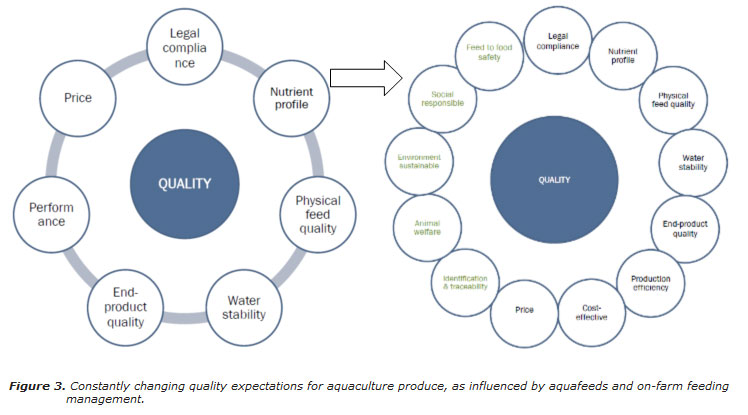

Constantly changing quality expectations (Fig. 3) are demanding prompt response from aquafeed manufacturers and aquaculture producers, confirming the need for management systems that provides structure for good communication and transparency – also to the consumer. There are numerous sources of information on the negative aspects of aquaculture that are easily accessible to end-product consumers. A formal management system promoting transparency and pro-active communication may help change such perspective and open new markets.

Quantifying and/or qualifying Responsible Aquafeed and On-farm Feeding Practices necessitate having a broad policy framework as roadmap that can assist in developing a good aquaculture practice manual, specific procedures on how to implement it and provide hands-on training and re-training, and a system of record keeping for proof and reference to ensure transparency and traceability.

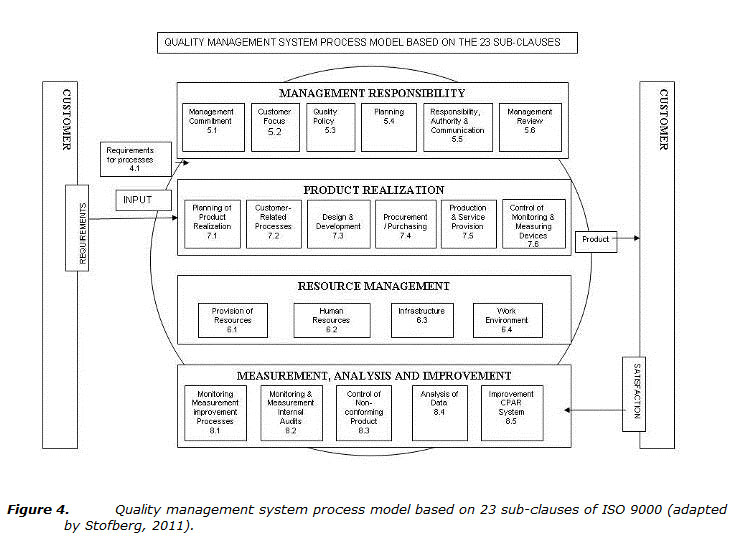

The aim of this document is to provide a generic basis that can be used to tailor-made Responsible Aquafeed manufacturing and on-Farm aquafeeding, to satisfy farm-specific needs and to provide a framework for a potential auditable management system. It is built on the quality management system process model for product realization (Fig. 4) – whether it is intended to feed-product (aquafeed) realization towards the farmer, or end-product (feeding management) realization towards the consumer.

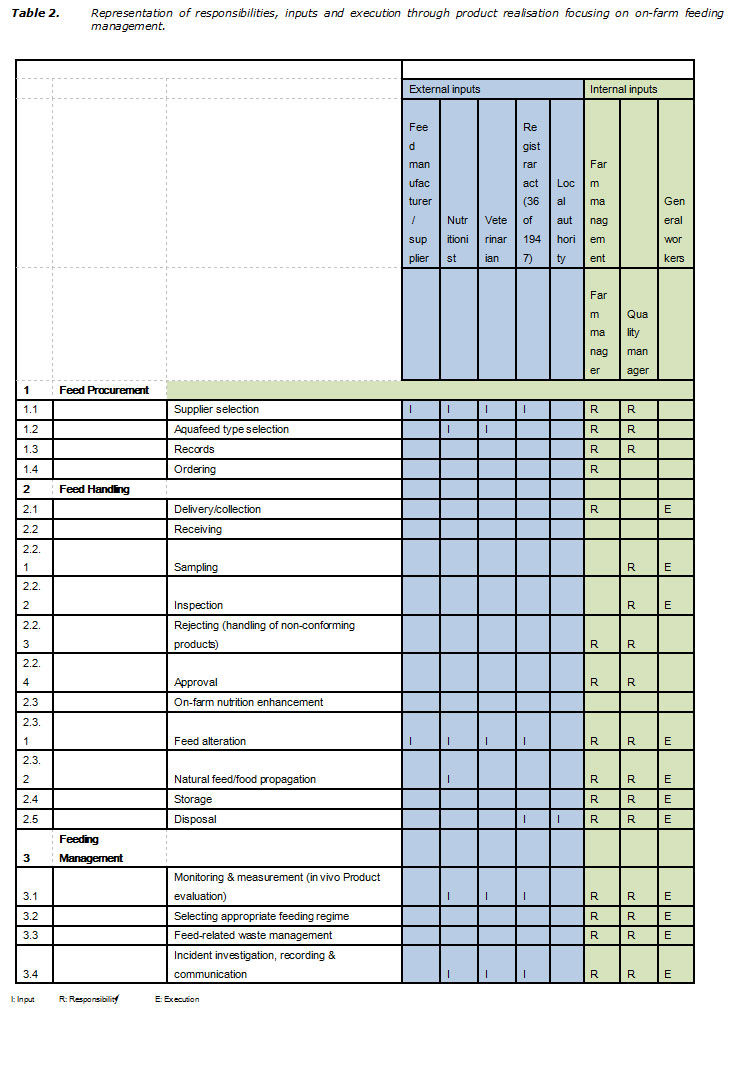

Throughout the guide, management responsibility refers to various external and internal input demands for specific section of the aquafeed manufacturing and/or feeding management process flow. The process flow indicates who is responsible for what action. However due to differences in management structure the intention is to provide an example that need to be customized for individual organizations. Table 2 serves as example of how a process flow could be developed implemented and management responsibility is identified.

Alder, J., B. Campbell,

V. Karpouzi, K. Kaschner, and D. Pauly. Forage fish: From ecosystems

to markets. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 33: 153–166 (2008).

Allsopp, M., P. Johnston, and D. Santillo. Challenging the aquaculture

industry on sustainability. Greenpeace International, Amsterdam,

the Netherlands, 24 pp. (2008).

Clover, C. The End of the Line: How Overfishing is Changing the World

and What We Eat. Berkley and Los Angeles, California: University of California

Press, 384 pp. (2006).

FAO. World agriculture: Towards 2015/2030. The Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 97 pp. (2002).

FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2008. FAO Fisheries

and Aquaculture Department, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations, Rome, Italy, 176 pp. (2009).

Hardy, R.W. Collaborative opportunities between fish nutrition and

other disciplines in aquaculture: An overview. Aquaculture, 177:

217–230 (1999).

Jackson, A. Responsible sourcing of fishmeal for salmon. Presentation:

Seafood Summit 2010: Changing Assumptions in a Changing World, 31 January–2

February, Paris, France (2010). Available from http://seafoodchoices.org/seafoodsummit/presentations.php

Naylor, R.L., R.W. Hardy, D.P. Bureau, A. Chiu, M. Elliot, A.P. Farrell,

I. Forster, D.M. Gatlin, R.J. Goldburg, K. Hua, and P.D. Nichols.

Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proc. Nat. Acad.

Sci. U. S. A., 106: 15103–15110 (2009).

Pauly, D., J. Alder, E. Bennett, V. Christensen, P. Tyedmers, and R. Watson.

The future for fisheries. Science, 302: 1359–1361 (2003).

Pauly, D., and J. Maclean. In a Perfect Ocean: The State of Fisheries

and Ecosystems in the North Atlantic Ocean. Washington D.C.: Island

Press, 175 pp. (2003).

Pauly, D. Aquacalypse now: The

end of fish. The New Republic, pp. 24–27, October 7 (2009). Stier,

K. Fish farming’s growing dangers. Time Magazine, September 19 (2007).

Tacon, A.G., and M. Metian. Fishing for aquaculture: Non-food use

of small pelagic forage fish-a global perspective. Rev. Fish. Sci.,

17: 305–317 (2009).

Welch, A., Hoenid, R., Stieglitz, J., Beetti, D., Tacon, A., Sims, N,

O’Hanlon, B. From Fishing to the Sustainable Farrming of Carnivorous

marine Finfish. Reviews in Fisheries Science, 18(3): 235-247 (2010).

Tacon, A.G.,M.Metian, G.M. Turchini, and S.S. De Silva. Responsible

aquaculture and trophic level implications to global fish supply. Reviews

in Fisheries Science, 18: 94–105 (2010).

Tydemers, P., N. Pelletier, and N. Ayer. Biophysical sustainability

and approaches to marine aquaculture development policy in the United

States. Marine Aquaculture Task Force, Takoma Park, Maryland, 42

pp. (2007).

Volpe, J. Dollars without sense: The bait for big money tuna ranching

around the world. BioScience, 55: 301–302 (2005)

www.worldwildlife.org/what/globalmarkets/aquaculture

Lansdell et al. 2010

WWF (2011). WWF’s position on aquaculture, WWF South Africa, January 2011

http://www.worldwildlife.org/what/globalmarkets/aquaculture/aquaculturedialogues.html