NEWSLETTER

Page 4

|

NEWSLETTER |

||

|

Page 4 |

||

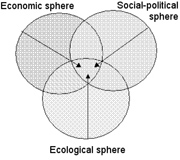

| A new model of sustainable development is needed | |

|

Sustainable

development is one of the most misunderstood and over-used concepts in

environmental decision-making today. More often than not it leaves those

tasked with implementing policy confused as to what course of action has

actually been decided upon. In

my opinion the heart of the problem lies with the three pillars model of

sustainable development. It draws a picture of three separate spheres: economic, social and

environmental - each with its own set of values and working according to

its own internal logic. The economic sphere is seen as aiming towards the

creation of material wealth and ensuring growth; the social sphere as

aiming towards improving the quality of life of people and ensuring equity

between people, communities and nations. While the environmental sphere

has to do with protection and conservation of our natural environment This

model of sustainable development strengthens the perception that aspects

of economic activity fall outside of the social sphere and also outside of

the environmental sphere, and that there is only some overlap in certain

areas. But there is not a single aspect of social life that does not lie

wholly in the environmental sphere, that does not have environmental roots

and consequences. In the same manner, all economic activity essentially

comprises social processes Nothing

is said in this model about the manner in which the three pillars interact

with or affect one another, or how they are dependent on one another. In

policy and decision-making, the interaction between the different spheres

is usually reduced to making trade-offs within and between the different

spheres – where costs in one sphere, for example the social or the

environmental, are offset by benefits in the economic sphere. A

far more realistic model of sustainable development is one where the three

separate pillars or spheres are embedded within one another. The widest

circle being environmental, the second circle being social and the central

one being the economic. From this point of view each wider circle serves

as a holding space for the sphere embedded within it, making it not only

possible but also sustaining it in the literal sense of the word. This

image further implies that activities in one sphere may have a negative

impact, even to the point of disruption or destruction, on the larger

sphere. The most important implication of the image of three embedded

spheres, however, is that economic, socio-political and environmental

considerations do not each have their own logic and values separate from

the other spheres. Rather they are intertwined from the outset – to such

an extent that a fundamental rethink is required of everything that we up

until now have conceptualised as economic activity, socio-political

engagement and the environment. PROF

JOHAN HATTINGH |

Another classic representation of sustainable development: The three pillars model

An alternative portrayal of sustainable development in terms of three embedded spheres |

| Local ethics committees should decide how much research participants are paid | |

|

Debate

has emerged in South African health research circles about what

individuals participating in research studies should be paid and who

should decide what that amount is. This is contentious because the payment

should reflect a balance between a

rate of payment that is high enough not to exploit subjects and low enough

that it does not create an

irresistible inducement that encourages people to take risks that may be too high. Views

on participant remuneration range from thoughts that research should be a

socially responsible activity with no payment at all to the view that a

wage payment model should be used in which research subjects are paid an

hourly wage based on that of unskilled workers. Most ethics committees in

South Africa allow an amount of R50 per visit to be paid for travel and

food expenses incurred by the participant for the study visit, and some

committees prefer that this amount not be reflected in the patient

information leaflet. However,

recommendations by the Medicines Control Council (MCC) require that

participants should receive R150 a visit for expenses incurred in

participation in research. The MCC states that the patient should be

issued with an information leaflet with this amount reflected before

deciding whether to participate in the research study. Just

how the money influences the patients decision to take part depends a lot

on the community being researched. A study in the Bishop Lavis and Elsies

River communities in the Western Cape who had participated in two

pharmaceutical industry-sponsored trials of an intranasal flu vaccine said

they used the money received primarily to purchase food for their

families, to transport themselves or a family member to a clinic or

hospital, or to meet cost-of-living expenses generally. In

this setting mentioned above, the standard of R50 per visit for three

study visits spread over 12 months was deemed acceptable – yet it is

likely that other communities with different economic backgrounds may have

substantially different views. The blanket compensation policy that is

being requested by the MCC ignores the complexities of each research project’s specific socio-economic context. In

general, health research ethics guidelines regard the issues of

participant remuneration as residing fairly in the domain of the research

ethics committee involved. We believe it should remain there to ensure that

a decision that best protects the interests of the participants involved

is taken. Summary

of article written by Keymanthri

Moodley and Landon Myer

and published in the South African Medical Journal on 23 September 2003 |

|